When the G20 Economy Challenges Our Vision of Global Health

One Health: A Double-Edged Approach?

For decades, our understanding of health has largely been shaped by the Pasteurian approach, which emphasizes hygiene improvements and reducing contact with microbes as the key to better health. Yet, despite significant advances in hygiene during the 20th century, the number of emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) has continued to rise. Increasingly, studies suggest that these outbreaks are linked to major environmental changes such as climate change, deforestation, urbanization, intensive agriculture, and biodiversity loss.

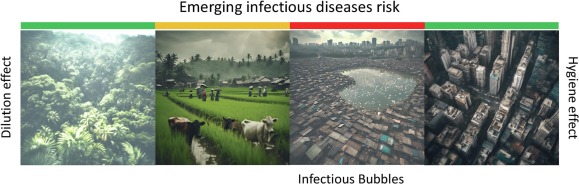

Consider, for instance, deforestation and agricultural intensification, which decrease the number of non-disease-carrying species while favoring animals that can transmit pathogens. This phenomenon, known as the “dilution effect,” shows that in ecosystems rich in biodiversity, the risk of infection is often mitigated by the presence of many non-host species. However, as diversity decreases, the transmission risks increase for species that survive and thrive in the absence of predators, such as urban rodents.

Since the 1980s, public health organizations, including the WHO, OIE, and FAO, have intensified their focus on the One Health approach, aiming to integrate human, animal, and environmental health. This perspective has led to the establishment of global research programs that analyze how ecosystems influence disease spread. However, the One Health approach faces a dilemma: how can we balance the need to incorporate more biodiversity and nature into our lives while minimizing disease risks?

Today, restoring biodiversity in urban areas, such as introducing more greenery and natural corridors in our cities, could also increase our exposure to the microbes present in these environments. These microbes, with whom we have co-evolved for centuries, could potentially lead to outbreaks or even pandemics. On the other hand, living in highly urbanized environments limits our contact with these microbes, which could weaken our immune system over time.

Thus, whether we favor an entirely urban lifestyle or reintroduce nature into cities, the risk of imbalance remains, raising fundamental questions for the One Health approach. The challenge is to find the right balance between human health, biodiversity, and risk management to create a future where cohabitation with microbes occurs without compromising our overall health.

Neglected Diseases at the Heart of the G20: Rethinking Global Health Through One Health

The “One Health” approach has gained remarkable traction, aiming to unify human, animal, and environmental health for a global perspective on health challenges. However, this perspective often encounters a misunderstanding: the tendency to pit “rich” countries against “poor” ones in terms of health, even though the definition of health goes far beyond this simplistic divide. According to the WHO, health is not merely the absence of disease; it encompasses complete physical, mental, and social well-being. A closer look, however, reveals that so-called “neglected diseases,” often associated with poverty, are also highly prevalent in the most developed countries, creating a true paradox.

Contrary to popular belief, parasitic infections are not absent from the world’s major powers. In the United States, for example, these infections persist, albeit rarely perceived as a significant threat. Paradoxically, G20 countries, among the wealthiest, account for the majority of neglected disease cases. Visceral leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, hookworm infections, and Chagas disease devastate millions of people. These so-called “tropical diseases” are actually linked to extreme poverty, regardless of geographic location.

This health divide has far-reaching consequences. Neglected diseases could contribute to the emergence of non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes, which are the leading causes of death in high-income countries. Several studies highlight the link between these infections and chronic conditions; for instance, schistosomiasis is associated with cancer, and Chagas disease remains a leading cause of heart disorders in Latin America. A shared understanding of emerging diseases between wealthy and poor countries is therefore crucial.

In response to this reality, the “Blue Marble Health” (BMH) concept has emerged to show that neglected diseases affect the poorest communities, whether they are in rich or poor countries. Unlike the pervasive poverty in some nations like Haiti, poverty in wealthier economies is concentrated in “pockets” of affluence, from Brazil to the United States. These “infectious bubbles,” located between urban areas and natural environments, are breeding grounds for diseases, fueled by poverty and biodiversity loss.

It is critical to integrate the concept of BMH into the One Health approach to address these vulnerable zones. Failing to do so would overlook the burden of neglected diseases in G20 countries and ignore the pivotal role of poverty in the spread of infections. Developed countries must recognize their role in creating these “infectious bubbles,” which, in addition to exacerbating inequalities, represent a public health risk to their own populations.

To move forward, healthcare and scientific stakeholders must rethink One Health by incorporating the Blue Marble Health concept. These neglected diseases could become key priorities for global health, prompting efforts to target these “infectious bubbles” at the intersection of poverty, biodiversity, and urban environments to prevent future epidemics and promote truly unified health.

From “Infectious Bubbles” to Urban Biodiversity: Rethinking Our Cities for Sustainable Health

“Infectious bubbles,” zones of poverty and degraded biodiversity where sanitation is insufficient, are among the most vulnerable to the emergence of infectious diseases. In a world where biodiversity is increasingly reintroduced into cities, a crucial question arises: can we reconcile the reintroduction of nature into urban spaces with the need to minimize health risks? A potential solution could lie in a balanced model that merges “hygienic” and “dilution” approaches. This vision proposes the creation of controlled biodiversity zones within cities, where local species play a role in regulating pathogens by offering a thoughtful mix of competent hosts (which can harbor pathogens) and non-competent hosts (which do not transmit them). These biodiversity spaces would act as buffers to protect human health, limiting the spread of diseases through dilution.

Several studies support this approach: for instance, an analysis of ecosystems where non-competent hosts were introduced showed a significant reduction in infection rates among competent hosts. These observations apply to various environments, from Hawaiian aquatic ecosystems to snail populations in Europe, demonstrating that host diversity can play a key role in pathogen regulation.

For governments and health organizations, incorporating these buffer zones into urban planning is essential, particularly in regions where poverty and degraded nature coexist. By creating pockets of biodiversity as safeguards against diseases, we could transform these high-risk bubbles into protective spaces. In addition to improving public health, this strategy would promote green economy jobs, reduce inequalities, and fight urban poverty.

In the decades ahead, strengthening urban biodiversity while ensuring health security will be a strategic challenge for sustainable and resilient urban health.