Exploring the Microbiome: Insights into Biodiversity and Disease with Université de Liège

In today's interview, we speak with Pauline Van Leeuwen, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Liège, about her work on microbiome profiling within BCOMING. Pauline’s research focuses on understanding how microbial communities in wildlife, particularly bats and rodents, influence disease emergence. She shares insights into her analysis of microbiome diversity, the significance of studying Rhinolophus bats, and the potential implications of her findings for biodiversity, public health, and environmental policies. Join us as we explore the critical role of microbiomes in shaping disease dynamics.

Interview

Can you please introduce yourself and give us an overview of the role that Université de Liège plays in BCOMING, and how your team is contributing to the project’s overall objectives?

My name is Pauline Van Leeuwen, I am a postdoc researcher at ULiege at Johan Michaux's conservation genetics lab. Our team is involved in BCOMING on the microbiome profiling of animals in Cambodia. This is an important aspect of one of the objectives of BCOMING on characterization of potential pathogens pool in wildlife and estimation of biodiversity. This information will also be included in the modelling steps to further understand mechanisms of disease transmission.

Your work focuses on understanding how biodiversity impacts microbiome structure, particularly in the context of disease emergence. How do you approach this analysis, and what unique insights are you hoping to uncover?

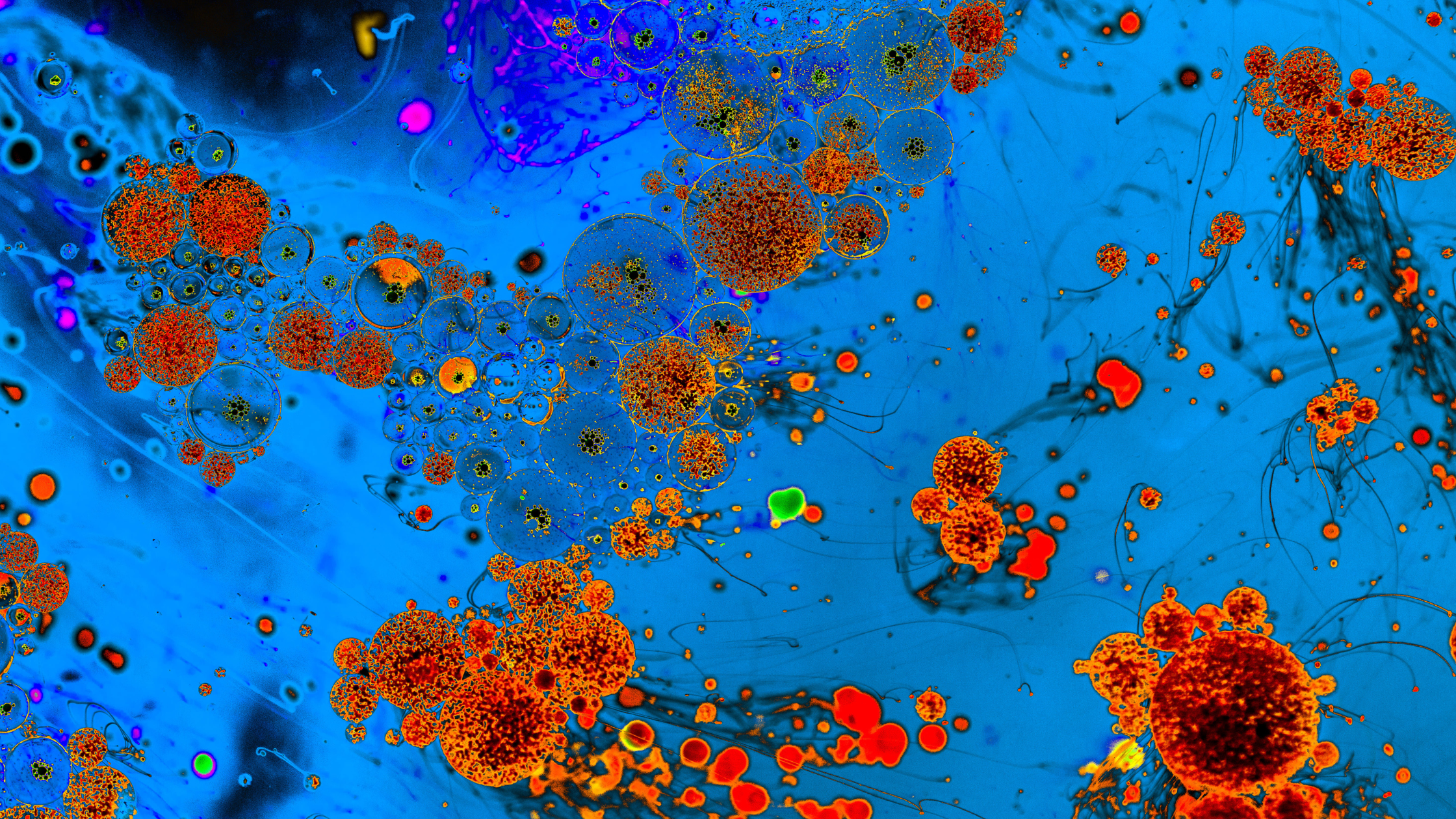

First, I think it's important to acknowledge that microbiome is part of biodiversity. In this project, we mostly evaluate microbiome as gut bacteria. We identify and quantify them through their DNA present in the feces of the animals. There are two main questions that I am interested in resolving. First, I want to see if those bacteria are more diverse in habitats where we can find multiple mammalian host species, meaning highly biodiverse habitats. And we could expect that fragmented habitats harbor more uniform microbial communities with few different species in high abundance and greater chances to be pathogenic. And second, I want to see if we can identify bacteria that are always present when a host is infected with coronaviruses and others that are not, in order to establish a blacklist of bacterial indicators for viral status and a whitelist that could be further studied to boost protection against coronavirus.

Rhinolophus bats are a key focus for your research, especially when it comes to correlating microbiome changes with viral infection status. Can you tell us more about the significance of studying this particular species, and how seasonal factors like diet and reproductive cycles influence your findings?

We are indeed focusing on rhinolophus bats, that are known reservoir of coronaviruses in the wild. We have some information that coronaviruses are more likely to circulate among juveniles and during pregnancy, which usually happens at the end of the dry season. Because this period is highly demanding in energy for the bats, we expect a shift in immunological response that will have consequences on the gut microbiome and viral status. We have few information on the diet of the species we are studying, and that’s why on top of the microbiome we will use the same samples to estimate the diet of each bat. That will allow us to garsp the ecology of the species and identify drivers of infections.

You’re also looking into how host-associated microbiome diversity varies across urbanization and domestication gradients. What kind of trends have you observed so far, and how do these gradients affect the presence or risk of viral infections?

For now, I haven’t had the chance to work on the samples because the sampling will take place early 2025, so it will be difficult to answer this question. However, we expect that we find greater risk of bacterial and viral infections in the fragmented and agricultural landscapes compared to the city and preserved habitats, especially in animals that we consider peri domestic, like rodents that travels between areas with humans and forested habitats. While we wait for Cambodian sampling, we are starting to analyze data from another region in Thailand (with our collaboration with Kasetsart University called the Spillover Interface project) close to a protected area and here as well you can see that rodents share similar bacterial pathogens with bats, but not so much with domestic dogs. More to come!

Looking at the bigger picture, what impact do you think the results of this microbiome research will have both within the BCOMING project and beyond? How might it influence future research, public health strategies, or even environmental policies?

To my knowledge it’s the first time that we include microbiomes within such a framework, and I hope it will at least encourage other researchers to think about how microbiomes should be included when it comes to assessing biodiversity. I truly believe that they are part of the story to understand the mechanisms that make disease emergence risk fluctuate. I hope to get results to lead a change in paradigm when it comes to microbiome science: we know that microbes are highly dependent on the environment, and that it changes when the host experience disease. I believe that there are specific communities/bacteria that can prevent disease and others that can trigger infection. If we find that, that will open plenty of possibility to unravel potential microbiome application to prevent infections.